Frost Giant

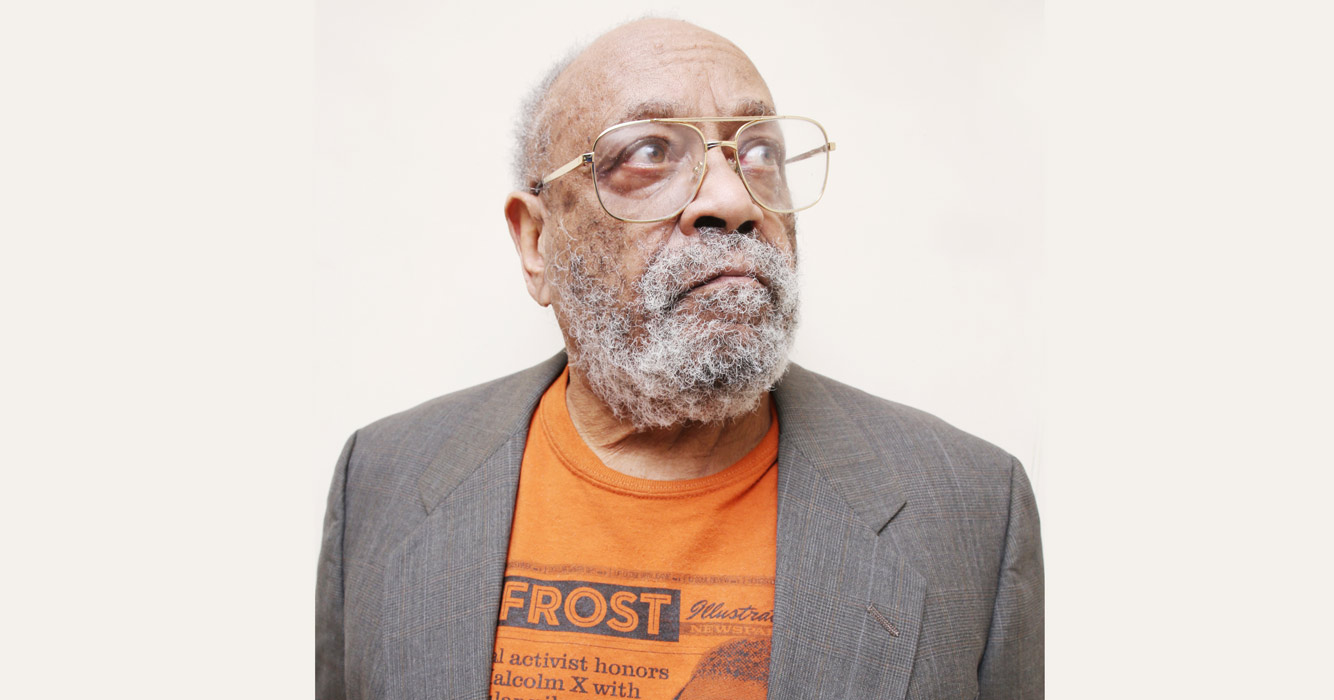

Written and Photographed by William Bryant Rozier

Frost Illustrated Newspaper, established in December 1968, has ceased printing the news and views of African Americans.

Frost’s last issue ever spanned the weeks of October 11 - 24, 2017. The headline story, written (presumably) by an uncredited Michael Patterson, the then managing editor, touts the hiring of the new Lutheran Hospital CEO, Paula Autry.

When asked why Frost Illustrated shuttered, Edward N. Smith, former co-publisher and owner, struggled for an answer. “I haven’t figured it out yet,” Smith said. Mistakes were made. Mistakes were always made. It’s a business. Edward N. Smith volunteered the story of that one time, back in the day, where he lost money for the newspaper by playing in the stock market. At the time, Smith had 1,000 shares of two stocks each, both valued at $10/share. He diverted funds from one to the other, acting on a hunch. The money invested was allotted for Frost Illustrated.

“I ended up buying 3,000 shares when the company [I invested in] was absorbed by debt. The one I should have kept was the motorcycle people, Harley-Davidson,” Smith remembered, laughing. “With my brilliant self.”

Smith’s two strokes in 2017 pulled him away from his co-publishing duties permanently. He asked his son, Edward Smith Jr., to take over. Smith Jr., a former firefighter, had worked at Frost, in some capacity, since high school.

Again, mistakes were always made. But the latest set of mistakes was too daunting for Frost to recover from. The missteps were coupled with occurrences beyond Frost’s control, like the poaching of their staff by bigger papers, according to Edward Jr. “We were a stepping stone.”

What felled Frost Illustrated Newspaper? It was a combination of mismanagement, a reduction in staff (particularly in the sales department), and the marginalization of the newspaper print business occurring both nationally and locally (see: The Fort Wayne News-Sentinel). Back-up plans for Frost, including finding outside investors, were explored and exhausted.

“I’m going to miss Frost, I really am. I understand what Frost is all about now. I can probably run a good paper,” Smith said. “I hate giving up Frost. But I can’t do it by myself.” At the age of 87, Edward N. Smith is a newspaper man now.

December 1968 (Vol. 1, No. 1)

Smith started Frost for his wife, Edna. “I was a lawyer,” Smith said; around 1960, the Smith family moved from Indianapolis to Fort Wayne, so Edward could start a private practice (personal injury cases mostly, some divorces). He relinquished his job at the state department, working for the governor, to work for himself. According to Smith, he wanted to insure that his wife had people working for her, in case something unintended happened to him.

The Smiths were married in 1948. Edna, on the day of the Edward’s interview, was in bed, watching television, suffering from the effects of dementia. He is still her steward. Mr. Smith’s own memory plays tricks on him these days. During his interview, he would apologize for the delays when responding but would often implore to keep going.

“I can’t think as fast as I used to, I’m having a hard time remembering things. I always liked giving interviews,” Smith said. “Come on, come on, give me questions! “You can ask me anything you want to ask me.”

In the beginning, “I didn’t know what I was doing,” Smith said. “I thought the newspaper business was simple. It wasn’t simple at all.”

Smith, who supplied the finances, initially partnered with Reverend White and Reverend Rice on the newspaper; he would later buy them out. Their first office was located where the Lincoln Life parking lot is on Calhoun Street.

One worker laid out the whole paper on a Monday at a cost of $250, according to Smith. Coupled with the price of printing and other expenses, he said it took a minimum of “$2,500 a week to run a paper. And that was real small.” When Frost began, there were two other black-owned newspapers in the city. One of the papers was called Coffee Break, owned by, according to Smith, “a gentleman by the name of Andrews. He was Joe Andrews’ son. Do you know who Joe Andrews is? Have you ever been arrested?”

Joe Andrews was a popular bail bondsman. Mr. Smith had trouble remembering the son’s name. Joe Andrews’ son, the owner of the Coffee Break, was once the recipient of a brand new printing press. But “he left it out in the rain for a year or two because he couldn’t fit it through the front door. (Laughs.) A very expensive printing press just rusted out there,” remembered Smith. “He didn’t know what he was doing.”

To develop content, Smith tried copying the editorial style of the Journal Gazette, but he wasn’t feeling it. “When I read the [Journal Gazette], all I read is the obituary section. I see the sports and the news on the television. They got a [storytelling] problem, and they’ll find that out eventually if they don’t do something different.

“Black newspapers don’t have that problem. You always find out something new. You always find out something about your neighbor.”

Smith hired students from IPFW and Ivy Tech to help write the stories that would eventually cater to Frost Illustrated’s new mission statement, to always oppose the blurred perception of African Americans put forth by a certain kind of media type. “Black folks get their picture taken when they rob a bank or something. It’s in the paper. Or when they’re giving something away,” Smith said. “We did the opposite, we wrote about black folks having dinner parties and picnics and everything.”

Stories in Frost featured African Americans at country clubs, with compliments to the dinner-party host. That house style remained. Eventually, the paper’s various managing editors infused their own styles. Writers and photographers found audiences.

(Full disclosure: This writer’s first freelance gig was for Frost back in 2003. I was a paid film reviewer, $50/article, until Mr. Smith got wind of it. I got paid $25 after that. Apparently I was bankrupting the whole operation. Thanks for the start, Mr. Smith.)

Black Excellence, Black Legacy

“I wish I was still in the newspaper business because it’s a good business.”

Edward N. Smith’s comments kept coming back to how he would run the show now. “The salesman is the most important part of the paper. That’s where all of the money comes from.” Smith remembered Frost’s two really good salesmen.

“One guy was excellent. He had files of names. Got so successful that he started going out with the ladies,” said Smith. “But then he started to slow down.”

The momentum of the storytelling swung back to his wife, Edna. “I never got the idea that I needed more than one salesman, never discussed it with my wife. I never got to tell her that she needed two or three salesmen.” Latissha Williams, Fort Wayne Ink Spot administrative assistant, and former Frost Illustrated employee, asked Mr. Smith for advice on the new publication. He made a joke about not having enough time to tell us.

He then softened his delivery. No more jokes. “What you need is to write the highlights of your life. Emphasize the man who owns a drugstore and what he had to do [to own a drugstore]. You do all of the businesses like that.” Edward Smith then volunteered to provide Fort Wayne Ink Spot with his old Frost subscription list. “Anything I can do to help you guys out,” Smith told Latissha.

“Can you do right by my subscribers? They were good to us.”

I run Scrambled Egg(s) Design and Productions, based out of Northeast Indiana. In addition to producing in-house company projects, I also create advertising materials for companies and organizations, with an emphasis on interactivity.