Southeast Neighborhoods Hit Hard By Pandemic

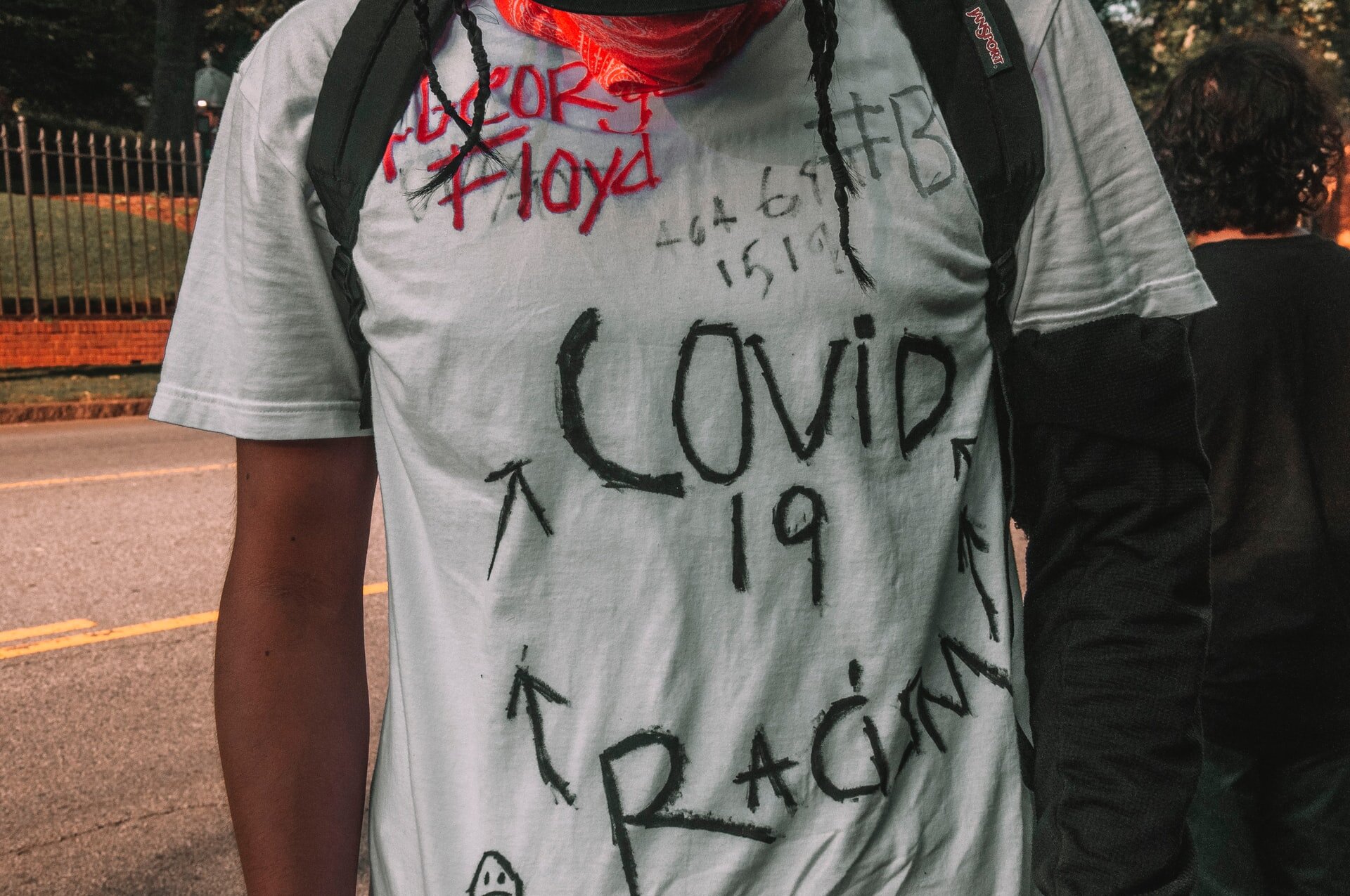

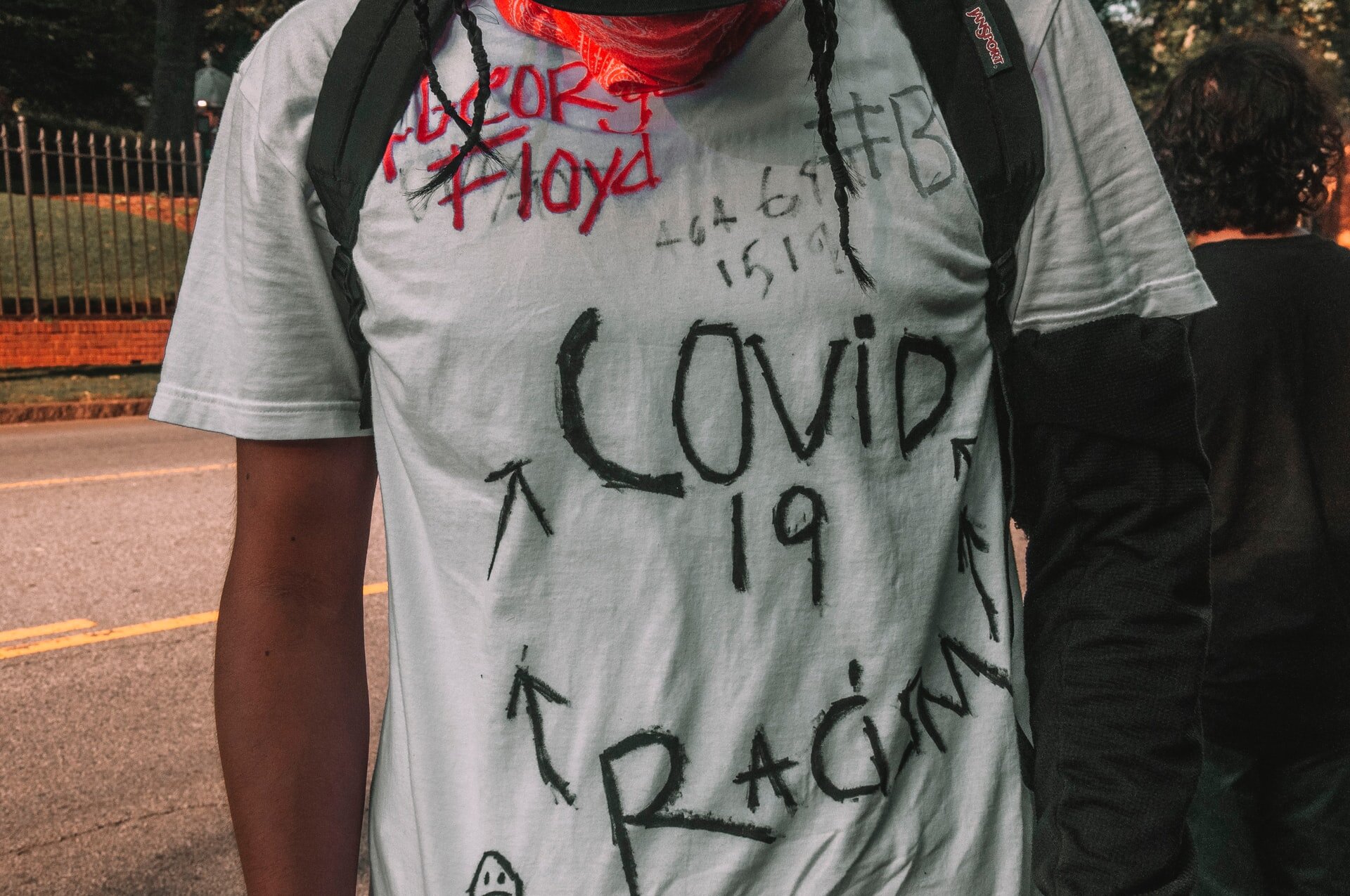

COVID-19 exposes institutionalized inequities that hurt people of color

By Fred McKissack

When it comes to COVID-19, Fort Wayne's Southeast neighborhoods report a high percentage of cases counts, according to an analysis of data.

This should come as no surprise, say public health experts, who add that local disparities track with national trends and point to this nation's history of structural racism.

Zipcodes 46803, 46806 and 46816 — all three have significant African American representation as well as higher rates of poverty — have a larger percentage of COVID-19 cases when compared to more affluent neighborhoods, according to the Indiana Management Performance Hub's COVID-19 Case Count database.

The data is based on a study released earlier this month by the Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis' Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health, which estimates that about 2.8 percent of all Hoosiers had been exposed to COVID-19. The report found that 45 percent of Hoosiers were asymptomatic — meaning they didn't realize they had been infected.

Drilling down into the data exposes the imbalance between various zip codes. (Readers can access the database at https://tinyurl.com/y8su93lt)

For example, 46806, the heart of the city's black community and one of the state's most impoverished areas, had 375 reported cases at the time of the survey, which represents 1.59 percent of the zip code's population. Further south, 46816 counted 286 cases or 1.58 percent of the zone's population. The state's data shows that COVID-19 had struck 1 percent of residents in 46803.

All three zip code areas fall well below the state's average adjusted gross income of $55,746.

By comparison, the residents of 46814, located in the city's southwest, is one of the state's wealthier areas with an average adjusted gross income of $176,240. Its COVID-19 case rate is 0.22 percent of the zone's population. [You might add something like: That is still higher than the state average, but the southeast side of Fort Wayne's rate is more than seven times higher than 46814's.]

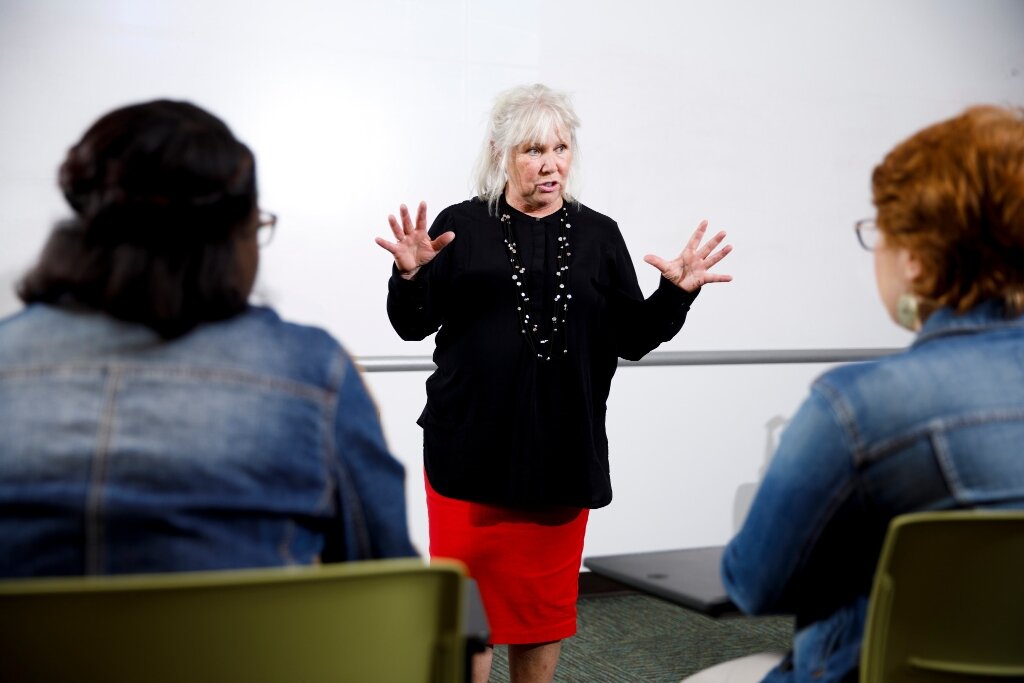

"COVID-19 is the perfect storm for health disparities," said Janet Ann Nes, clinical assistant professor of social work at Indiana University Fort Wayne. "You have marginalized communities with a poverty of resources."

COVID-19 has exposed the obvious, but overlooked intersection of race, socio-economic background and health, said Nes, who also coordinates IU-Fort Wayne's masters of social work program.

African Americans, Asians, Latinos and First Nations peoples are indeed over-indexed in terms of cases and deaths during this pandemic. However, it's not biological, but rather the virus is attacking people who have suffered through long-neglected societal issues, experts say.

These challenges were discussed at length during a recent online seminar by the Indiana University Bloomington School of Public Health titled "COVID-19: Health Disparities, Communities, and Discrimination."

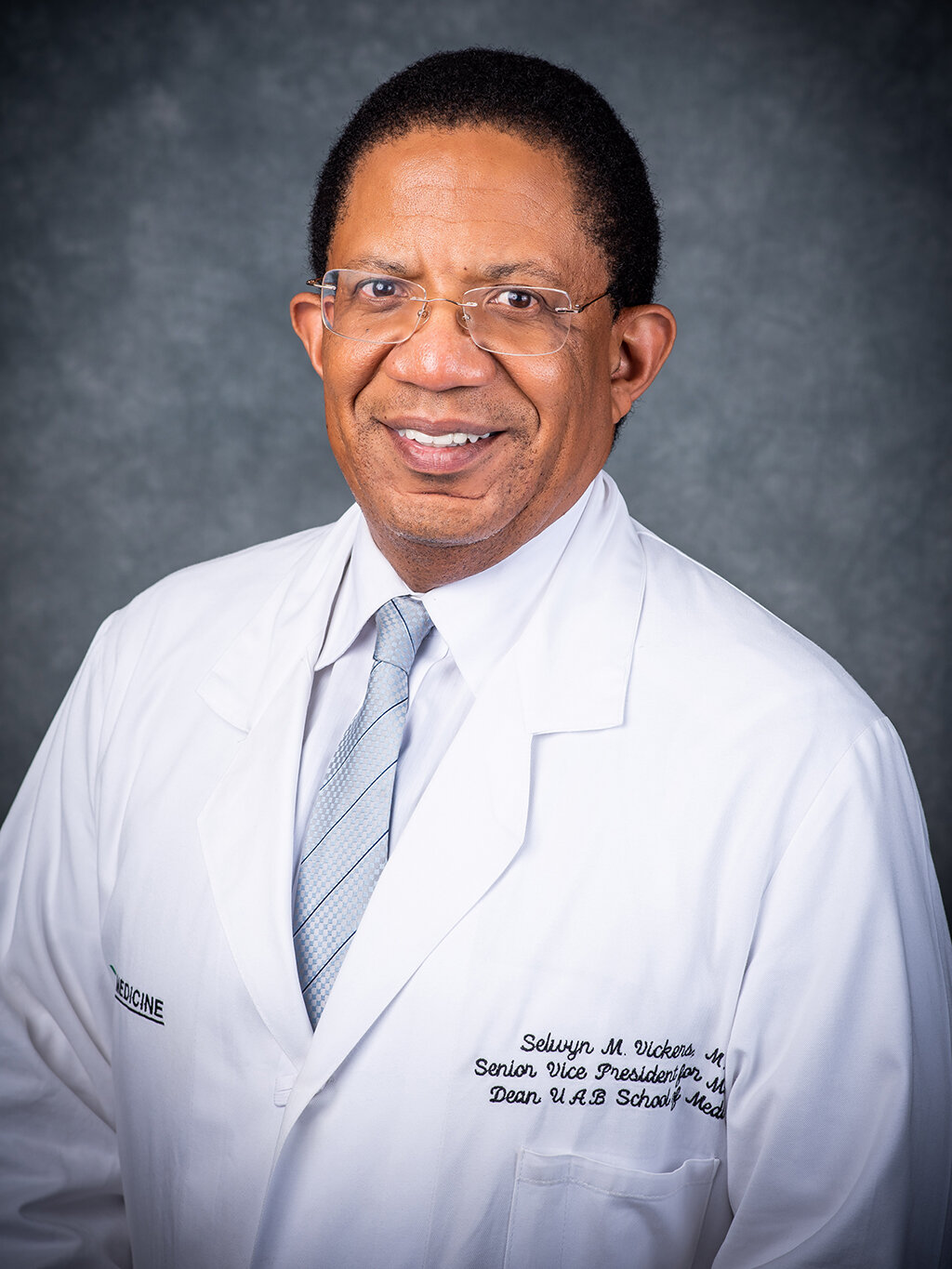

"We've never seen lethalities linked to a disease as we've seen with this," said Selwyn M. Vickers, M.D., senior vice president for Medicine and dean of the School of Medicine at the University of Alabama Birmingham. He is also an executive of the Society of Black Academic Surgeons.

Dr. Vickers contrasted the violent deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery and the racial disparities in cases and deaths of COVID-19. In both cases, blaming the victims ought to assuage this country's complicity in institutional and structural problems "that have been a long-standing sin for our country," Vickers said.

Poorer areas suffer from a poverty of resources, such as access to health care, combined with a higher population density. Food deserts are a factor; the exclusion of quality produce leads to higher levels of comorbidities such as diabetes, obesity and heart disease. Combined with COVID-19, these patients face a higher risk of death than healthier people.

Lack of insurance and a scarcity of family care physicians possibly contribute to the higher numbers, said Nes of IU Fort Wayne, particularly during the pandemic's early days when access to testing required potential infected residents to be referred by a physician.

Residents in these neighborhoods tend to work in industries that don't lend themselves to working at home. An increased number of touchpoints — including the use of public transportation — only adds to the risk of infection.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, nearly a quarter of African American workers are employed in service industry jobs compared to 16 percent for non-Hispanic whites. African Americans account for 30 percent of licensed practical and vocational nurses.

Toxic environments are also a risk factor and strike not just poorer people of color, but also people who are solidly middle class, according to a recent article on the website of Nature, a respected science journal.

"African Americans who earn US$50,000–60,000 annually … are exposed to much higher levels of industrial chemicals, air pollution and poisonous heavy metals, as well as pathogens, than are profoundly poor white people with annual incomes of $10,000," explains the article's writer, Harriet A. Washington. "The disparity exists across both urban and rural areas."

The worst pandemic in a century rages on with hopes pinned on a vaccine to be distributed by 2021. Meanwhile, public health officials are already worried about this fall's flu season colliding with COVID-19, crushing intensive care units that will also need to deal with other life-threatening emergencies ranging from accidents to heart attacks, thus forcing the rationing of life-saving treatment.

America will survive COVID-19. However, there needs to be a reckoning of the societal inequities that are endemic in the current system, experts said.

"We have to recognize that healthcare is a human right," said Nes. "Here in the United States, we view it as a privilege. As long as we hold on to [the latter] and not accept it as a human right, we're going to see this problem happen again and again."

To allow the system to continue with these inequities is intolerable, said Dr. Vickers.

"It's our greatest challenge ... access to care," Dr. Vickers told the seminar's attendees. "We cannot afford for either ourselves or our closest allies to sit on the sidelines and be quiet in the face of injustice."